Nowadays, good electric cars already have enough range for most people, but they are still much more expensive than their ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) counterparts. This is why LFP (LiFePO4) and CTP (cell-to-pack) are extremely important technologies to make electric cars mainstream. Automakers that don’t plan to use these two technologies as soon as possible aren’t serious about mass producing electric cars. For example, Stellantis plans to start using CTP packs with LFP cells only by 2024…

LFP is a cobalt-free battery chemistry that combined with simple CTP batteries can finally make electric cars compete with ICE cars on price and availability.

While at the cell level the energy density isn’t great, at the battery pack level LFP can compete with other chemistries. Since LFP is a very safe battery chemistry and cells don’t burn or explode even if punctured, battery packs don’t require much protective equipment. Therefore, LFP battery packs are extremely simple to assemble and can adopt a module-less CTP configuration.

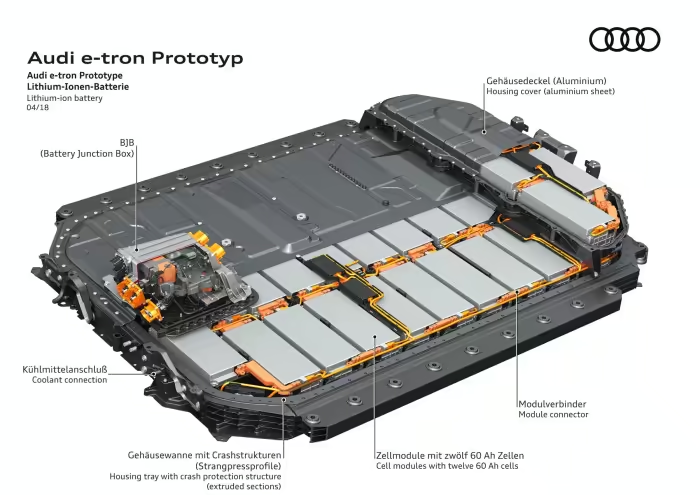

As for common NCA and NCM cells, they are more energy dense, but aren’t very safe. Battery packs made with these cells require modules and metal plates to act as firewalls in the case that a cell burns or explodes.

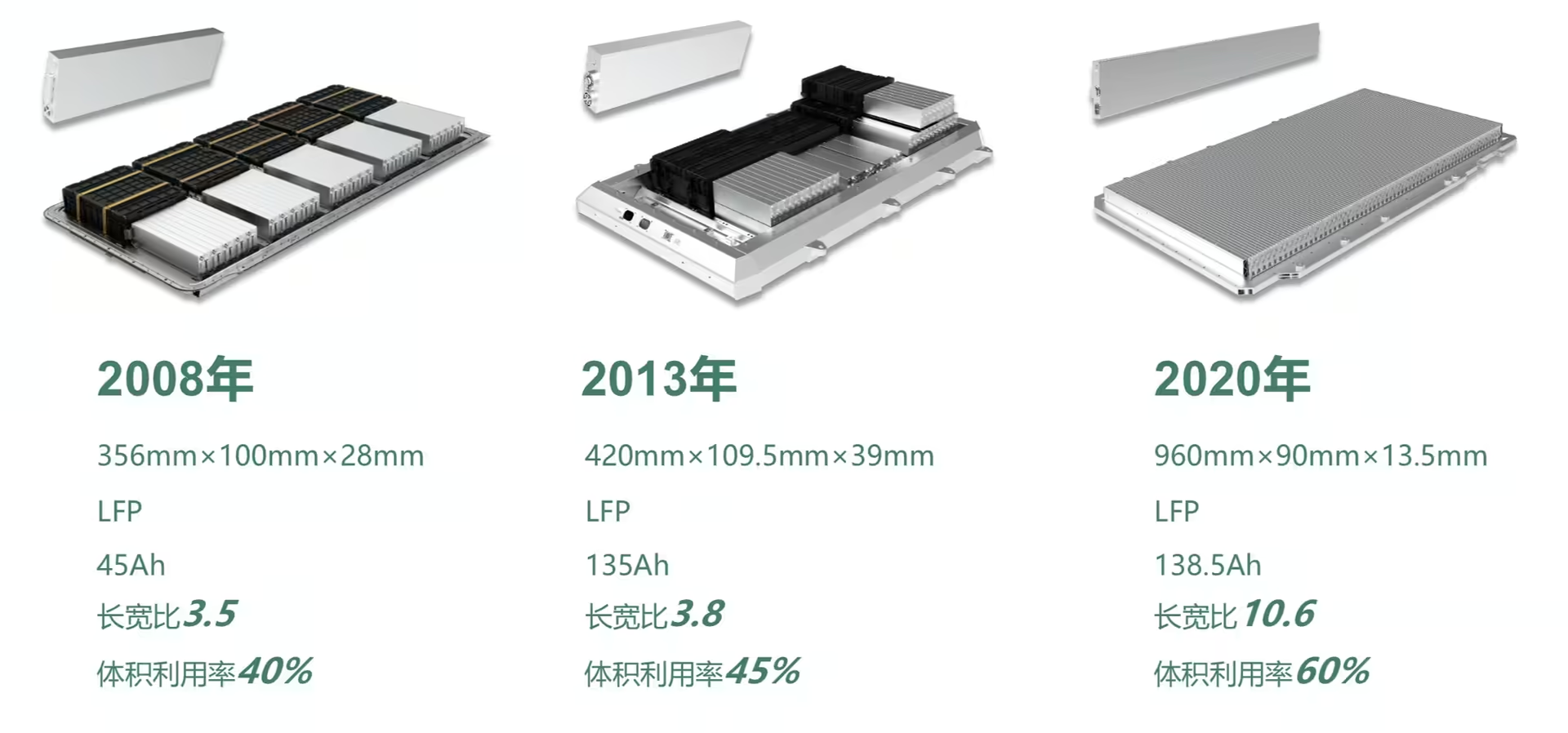

Summing up, with super safe LFP battery packs the VCTP (volumetric cell-to-pack) and GCTP (gravimetric cell-to-pack) ratios are much higher. Let’s see some average figures.

LFP battery packs

- VCTP ratio: 60 %

- GCTP ratio: 85-90 %

NCM/NCA battery packs

- VCTP ratio: 40-45 %

- GCTP ratio: 60-65 %

The VCTP ratio tells us how much of the battery pack’s volume corresponds to active material - that actually stores energy (cells). The rest of the volume is from the passive material used to assemble and protect the cells (case, modules, cables, sensors, BMS, TMS, etc).

The GCTP ratio tells us how much of the battery pack’s weight corresponds to active material - that actually stores energy (cells). The rest of the weight is from the passive material used to assemble and protect the cells (case, modules, cables, sensors, BMS, TMS, etc).

As you can see, not only the NCA and NCM cells are by themselves more expensive than LFP, their battery packs are also much more complex and require expensive material to make them somewhat safe. Only around 45 % of the volume is used by active material (cells), which means that the passive material required to assemble and protect the cells takes most of the space.

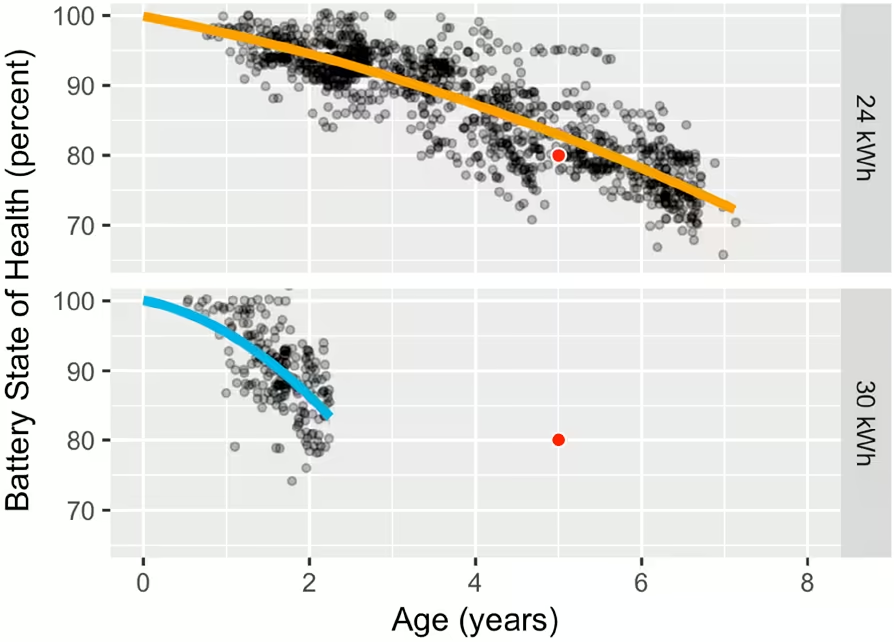

Below you can see the simplicity that BYD achieved in 2020 by removing modules with the introduction of its Blade battery that follows a CTP configuration.

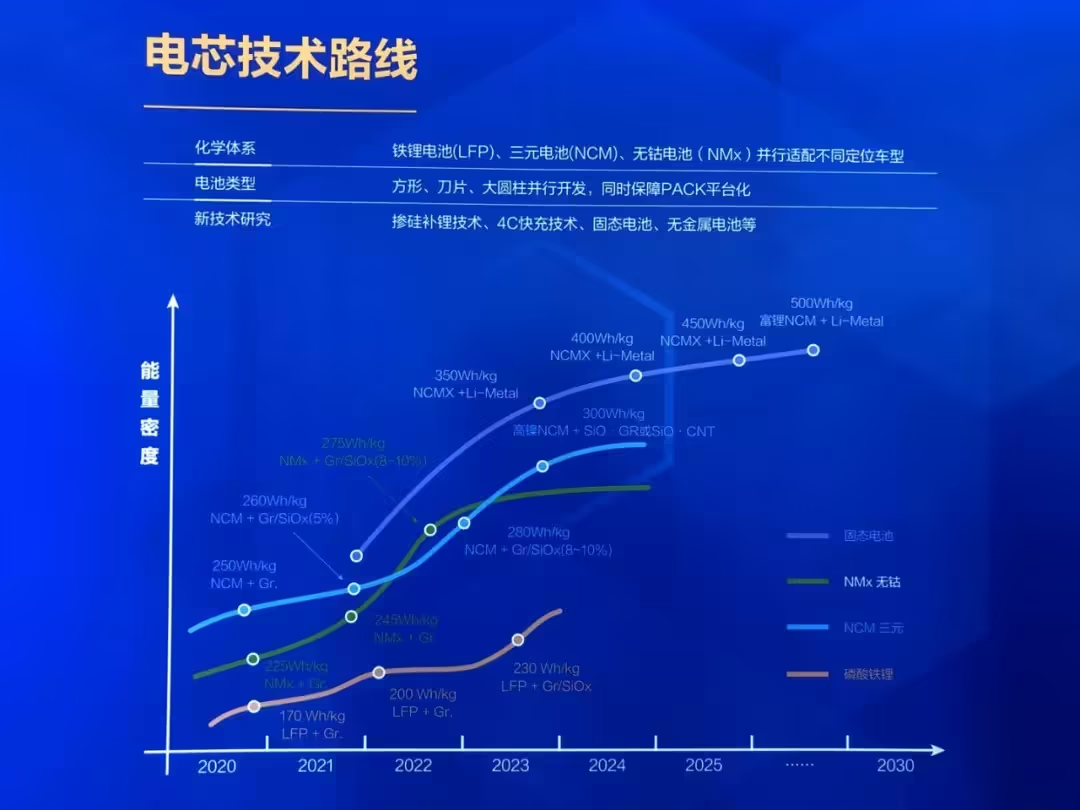

Moving on, let’s see what kind of energy densities important battery cell makers expect to soon achieve with LFP battery cells.

SVOLT

- 2021: 170 Wh/kg (graphite anode)

- 2022: 200 Wh/kg (graphite anode)

- 2023: 230 Wh/kg (hybrid graphite/silicon anode)

SVOLT expects to increase the energy density of LFP cells by adding more silicon to the graphite anodes.

Guoxuan

- 2021: 230 Wh/kg (207 Wh/kg at pack level with JTM)

- 2022: 260 Wh/kg (234 Wh/kg at pack level with JTM)

Guoxuan expects to increase the energy density of LFP cells by replacing graphite with silicon in the anodes.

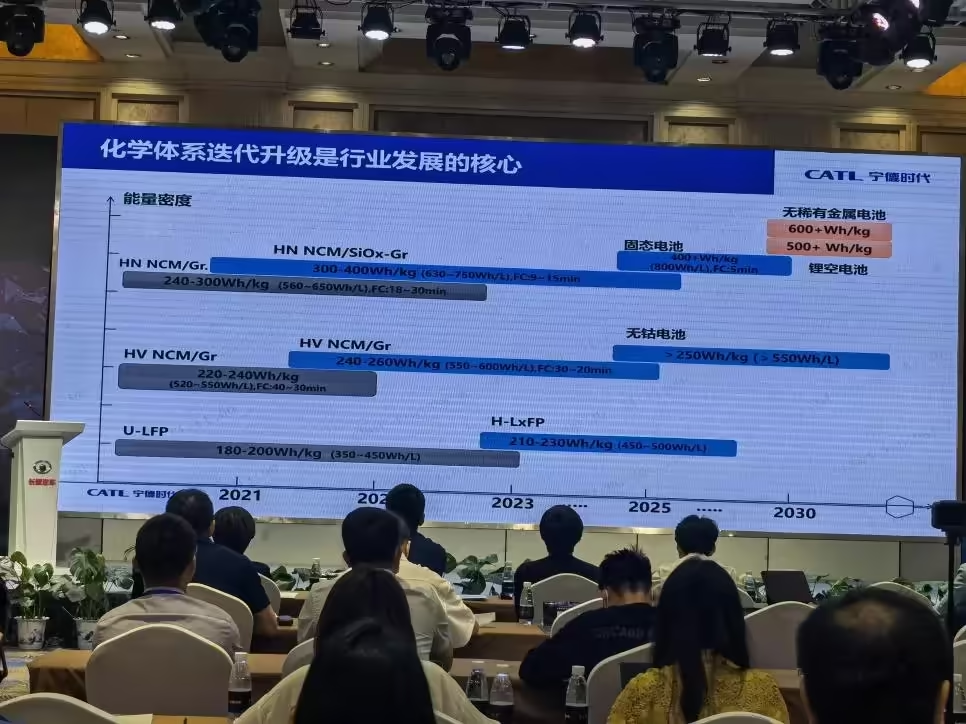

CATL

- 2021-2023: 180-200 Wh/kg (350-450 Wh/L)

- 2023: 210-230 Wh/kg (450-500 Wh/L)

By 2023 CATL expects to introduce the LxFP battery chemistry, which is probably the high-voltage version of LFP (LMFP/LFMP) that I have been writing about for some years.

By now you probably know that the BYD Blade battery is my favorite battery pack design. I cringe every time I watch a video of Sandy Munro tear down a battery pack from legacy automakers. There is so much junk in there that could be avoided with a simple CTP battery made with LFP cells. Imagine how simple and fast can be the production lines that assemble CTP batteries.

When first released in 2020, the BYD Blade battery achieved an energy density of 166 Wh/kg at the cell level and 140 Wh/kg at the pack level. However, LFP chemistry has been improving since then and I wonder how energy dense will be the second generation. If BYD reaches 200 Wh/kg at the cell level, the Blade battery pack can reach 170-180 Wh/kg.

I’ll be disappointed if by next year BYD doesn’t use silicon as anodes for faster charging and reach at least 170 Wh/kg at the pack level.

The imminent arrival of BYD e-platform 3.0 is a good opportunity to introduce the second generation of Blade battery. I’m curious to know the energy density of the battery pack used in the upcoming BYD Dolphin.