The Dacia Spring is the by far most affordable battery-electric vehicle on sale in Europe, typically starting under €20,000. It was also Europe’s 9th bestselling battery-electric vehicle (BEV) in 2023, registering almost 60,000 units. Where are the Dacia Spring’s competitors? The legacy auto brands are for the most part refusing to make affordable BEVs, so what’s available in China, and will it come to Europe?

Dacia is owned by Renault Group, and the Spring is made in China by Renault’s local partner Dongfeng. The Dacia-branded car is only marketed in Europe, where it has been on sale since H1 2021. Dongfeng Renault and Dongfeng have sold the same underlying vehicle in China since 2019, first marketed there as the Renault E Nuo, the Venucia E30, and the Dongfeng EX1 (amongst other names).

The currently most prominent variant of the car on the Chinese market is the Dongfeng Nano Box, which recently had a styling and interior refresh, and is selling at volumes of close to 1,000 units per month (and ramping). Yet, this is just a fraction of the car’s sales in Europe. Why are its sales not higher, given that China’s BEV market has nearly three times the volume of that in Europe?

While the car currently stands alone on relative affordability in Europe, this is not the case in the Chinese market. Amongst the 230 different BEV models available in China, the Dongfeng Nano Box competes against many alternatives with directly comparable range and features.

In this article series we are going to have a look at these alternatives to the Spring and its Chinese twin. Are any of them likely to come to Europe and boost the competition in the segment of affordable BEVs?

Pricing: The Dacia Spring & The Dongfeng Nano Box

Let’s first understand pricing. The European pricing of the Spring varies by country, according to what incentives are on offer. Dacia increases the price if the purchaser can access local incentives. For example, in Germany, where the “eco-bonus” incentive has recently been cancelled, the Spring is now priced at €12,750 (which they are marketing as a temporary discount from “normal” MSRP of €22,750). In Spain, where purchase incentives still exist, the same vehicle is priced at €18,920. At these prices the Spring is only “affordable” relative to other BEVs — similar sized ICE cars are priced from around €10,000.

The same car in China, the Dongfeng Nano Box, has an MSRP of €9,043 (70,700 RMB), including the same 26.8 kWh (gross) battery as we find the Spring.

However, deals on the Nano Box can be had for 54,700 RMB, or €6,996, for the same 26.8 kWh variant. Note that just like in Europe, the prices in China already include local VAT and applicable purchase taxes (although EVs are currently exempted from purchase taxes, so long as they are priced under 340,000 RMB, roughly €43,340).

Bear in mind that these are the prices of the Nano Box after its recent refresh, whereas the Dacia Spring’s pricing (above) is for an interior which is now 4 years old. What’s the difference? Well, let’s have a look at some photos, since the Dacia Spring is about to be refreshed also, and has been previewed as “the new Spring” coming to market in a few months time. Here are some exterior shots that show the styling differences (in order: current Spring, new Spring, Nano Box):

Here’s a view of their interiors, in the same order (current, new, Nano Box):

We can see that both the Nano Box and the new Spring have more modern interiors, and larger, floating infotainment screens.

What Are The Competing BEVs In The Home Market?

What are the Nano Box’s (and thus the Spring’s) main competitors in China? We’re looking for at least ~27 kWh battery, a ~33 kW motor, and able to DC fast charge to 80% in roughly 30 minutes. Why are we looking for Spring-like specs as a starting point? Although very modest compared to the expensive BEVs in Europe, the Spring is about the minimum specification that can, with some patience, just about handle all-round duty for many (if not all) drivers. It can do the usual daily local errands, school run, and commuting, but it can in principle also do occasional (“unhurried”) longer journeys with DC charging refills along the way.

The CLTC (China light-duty vehicle test cycle) range rating for the Dacia-Dongfeng twins is just over 300 km (the CLTC is an urban-centric cycle which is unrealistic for European mixed driving). The Spring’s WLTP urban cycle rating is 302 km, and WLTP combined cycle rating is 230 km. For longer drives in Europe, the real-world range at modest highway or national route speeds (not much over 110 km/h) is around 150 km, in decent conditions. These aren’t cannonball-run vehicles, but with a charging-and-meal break, they can take a young family on a daytrip to the beach, or to visit a relative who lives a couple of hours away.

Besides battery size and charging, we’re also looking for models which at least roughly match the length of the twins, at 3,732 mm long. For context, this makes the twins a bit longer than the original Volkswagen Golf, and almost exactly the same length as the 3-door version of the original Toyota RAV4, or as the current Smart Forfour.

Given these characteristics, checking all of the 230 BEV models on sale in China, the twins’ immediate peers are the base BYD Seagull (aka Dolphin Mini), and the Leapmotor T03.

BYD Seagull

The BYD Seagull (aka Dolphin Mini) is already a celebrity, being the 7th bestselling BEV in the world in 2023, and 4th bestselling in China, despite only having launched in April last year.

It is 3,780mm in length, and has a base battery slightly larger than that in the twins — 30.08 kWh in the entry level Seagull. It can charge to 80% in around 30 minutes and has a CLTC range of 305 km.

This 30.08 kWh version has an MSRP starting from 69,800 RMB, or €8,930. Given the high demand for the Seagull, it is hard to find discounted deals below MSRP right now. Note that there is also a 38.88 kWh option, priced at 89,800 RMB, or €11,490. All versions have a 55 kW motor, a good bit more powerful than the twins’ 33 kW motor.

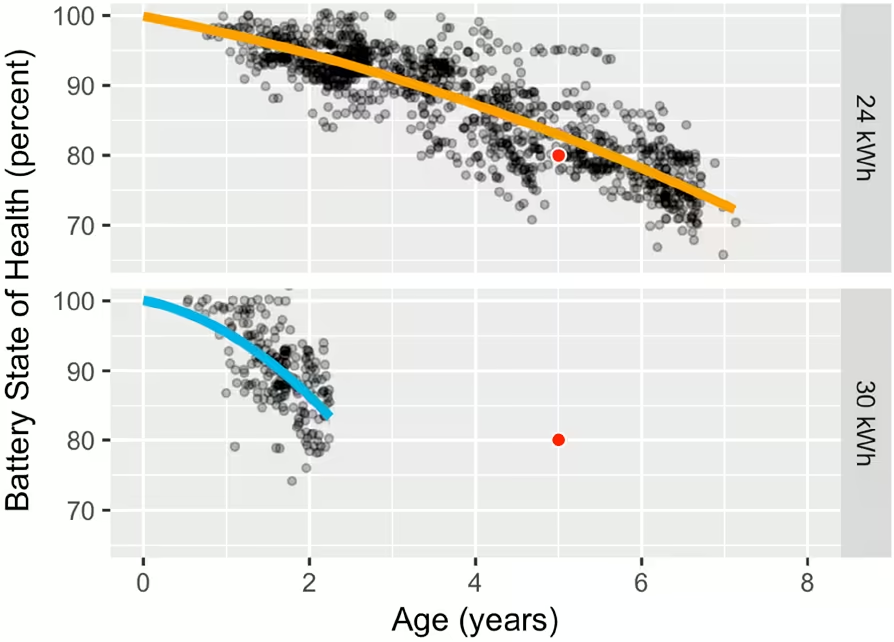

The BYD Seagull is currently selling around 30,000 units per month (!) in China, compared to a bit under 1,000 per month for the Nano Box. Perhaps BYD’s whole-vehicle warranty of 6 years or 150,000 km is helping, since most peers have a 3-year, 120,000-km vehicle warranty. (Note that like in Europe, all BEV batteries are warrantied for 8 years in China).

Leapmotor T03

The other close peer of the Dacia-Dongfeng twins, is the Leapmotor T03. This is another 4-door hatchback, with a similar format as Europe’s Smart Fortwo, with length of 3620mm, or about 10 cm shy of the twins. It launched in 2020, so is a bit newer than the twins (2019), but older than the BYD Seagull.

The variant with the closely matched 31.9 kWh battery (and DC fast charging) has an MSRP of 69,900 RMB, or €8,940. However, as with the twins, deals can be had for a good bit lower, in this case, with market prices around 59,900 RMB, or €7,660.

Even larger battery variants of the T03 are available, albeit at higher prices. The current largest battery option is 41.3 kWh, which (when optioned with DC fast charging) has an MSRP of 80,900 RMB, or €10,340. Deals can be found from around 70,900 RMB, or €9,065.

Like the BYD Seagull, the Leapmotor T03 has a 55 kW motor, so it is more powerful than the twins. However, unlike the Seagull, it has a more conventional 3-year, 120,000-km overall vehicle warranty (with 8 years on the battery).

The Leapmotor T03 is very popular in China, recently selling at close to 5,000 units per month. It is already on sale internationally, in countries as far afield as Chile, Indonesia, and Turkiye, amongst others.

Interestingly, Leapmotor and Stellantis recently entered a partnership to market Leapmotor’s vehicles outside China, and will assemble units in Europe, so the T03 is coming to the region soon.

There are a couple of other BEV models that could be considered close competitors of the Dacia-Dongfeng twins. For example, the Changan Benni is the same length and has a 30.95 kWh battery option (with 45-minute DC charging), and a 55 kW motor, for 79,900 RMB, or €10,240 MSRP. Deals can be had for 72,700 RMB or €9,320.

The Benni is built on an older platform dating back to 2010 (like the Nissan Leaf and Renault Zoe), and has been sold in variously-named BEV forms since around 2015.

Similarly, the Sehol E10X (currently marketed as the Sehol Flower Fairy) is based on a platform dating back to 2010. Variously-badged EV versions of the platform have been on sale since 2016, though upgraded and refreshed several times. The current Sehol E10X iteration was debuted in 2021. It offers a 30.2 kWh version (with 45-minute DC charging), and a 36 kW motor, for a MSRP of 71,900 RMB, or €9,220. Not many sub-MSRP deals can be found for the E10X.

Note that Sehol is a joint venture brand, created in 2018 by Volkswagen Group’s SEAT and JAC Group. This begs the question — why hasn’t VW Group followed Renault Group and brought this affordable BEV to Europe?

The Benni and the E10X are decent vehicles and were popular in their heyday, but are coming toward the end of their lifecycle due to their aging platforms. This, and their slightly slower DC charging speeds, means that I am not ranking them on the same level as the Seagull and T03 we have looked at above.

Not Minis?

Some of you may be asking, how about the Wuling Mini and other tiny BEVs, don’t some of them come with decent sized battery options these days? Yes they do. The Wuling Mini has a 26.5 kWh option and can DC charge to 80% in around 35 minutes (MSRP 62,800 RMB, or €8,040).

The Baojun Yep and the Changan Lumin have similar battery and charge options (at MSRPs of 79,800 and 69,900, respectively). All the other mini BEVs on the market either don’t offer such decent sized batteries, or don’t have practical DC charging speeds (or both).

Even for the few mini BEVs that do offer decent batteries and charging, notice that the pricing for these “big” battery variants is close to or above some of the other models we’ve looked at. This is a common issue in the auto market — the upper trims of models in one segment are often more expensive than the modest trims of models in larger segments.

But there’s a more intractable problem. The mini BEVs are at least 400 mm shorter in length than the Dacia-Dongfeng twins and the other BEV models we have looked at. More precisely, they have wheelbases of barely 2,000 mm (and less in the case of the Lumin). This is a shorter wheelbase than the original 1959 BMC Mini.

In practice, their small wheelbase, combined with their engineering intent to be used at modest urban speeds, means the minis are outside their element if called on to do highway speeds. Have a look at some review videos and note the frequent comments on their “imprecise” steering and stability when driven faster than modest urban speeds, if you remain unconvinced.

If only ever required for use at urban speeds, as they typically are in China, these minis are great value BEVs, no doubt. They can’t quite handle all-round duty, however, in the way that the Dacia-Dongfeng twins can just about manage.

Why Not Go Bigger?

Having mentioned the point that upper trim models of one segment often blur the boundary with the next segment above, why not look for potential competition for the twins at similar prices in the next size segment up?

As we step up in length from the twins’ 3,732 mm to 4,000 mm, several more models — with batteries at least as big, and similar DC charging speeds — present themselves. The best value amongst them include the Geely Geometry E, Neta Aya, Wuling Bingo, and even a younger brother of the Nano Box, the new Dongfeng Nammi 01.

Perhaps surprisingly, for the battery size we are looking for, all of these models have MSRPs of under 75,000 RMB, or €9,770, and deals can be found for considerably less!

The most compelling models currently offered in this larger 4,000 mm segment are the Geely Geometry E, Neta Aya, Wuling Bingo, and new Dongfeng Nammi 01. Let’s now find out more about these affordable BEV models.

Geely Geometry E

The Geely Geometry E is a subcompact crossover, with a length of 4006 mm, making it 27 cm longer than the twins (3,732 mm). For context, the Geometry E is about the same length as the current Volkswagen Polo and the Renault Clio, and a bit longer than the Peugeot 208. Being a crossover, the Geometry’s height is 1,550 mm, about 15 cm taller than those Europeans stalwarts (though similar in height to the twins).

The Geometry E was launched in 2022 and has recently been selling around 3,500 units per month in China.

The Geometry E offers a 29.67 kWh battery, with 30 minute DC charging, for 69,800 RMB, or €8,930. Deals can be found for 65,800 RMB (€8,440).

As well as being a bit larger than our Dacia–Dongfeng twins, the motor is more powerful at 60 kW (versus 33 kW for the twins). The CLTC rated range for this battery is still just over 300 km, so its trip capability between DC charges is modest, around 150 km at highway speeds, but matches that of the twins.

There’s also the option of a larger 39.3 kWh battery for 84,800 RMB (€10,880) for those wanting ~33% more range. Deals on this one can be had for 79,800 RMB (€10,245).

All variants come with a 4 year, 100,000 km vehicle warranty (and the usual 8 year battery warranty). As with all these models, there are plenty of video reviews to be found online if you want more of a feel for the Geometry E.

Some Geely badged vehicles are on sale in parts of Europe already (e.g., Serbia), but the Geometry E is not (yet?) offered. Perhaps the Geometry E could be badged as a Smart (one of Geely’s other brands) and brought to Europe that way.

Neta Aya

The Neta Aya is of a similar form factor to the Geometry E, and also very close in dimensions (length 4,070 mm, height 1,540 mm), and about 30 centimetres longer than the Dacia–Dongfeng twins.

The current Aya model is an update on the Neta V, which launched in 2020. The Aya sells around 2,000 units per month in China. It is also on sale in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and other countries in SE Asia.

The Aya comes with a base battery of 33.9 kWh and DC charging in around 30 minutes. CLTC range on this version is 318 km, and should slightly exceed the twins for real-world range, on those occasional days out.

The Aya’s motor power is 40 kW, lower than the Geometry E’s, but higher than the twins’. The MSRP for this entry version is 65,800 RMB, or €8,450. Deals, however, can be found for 58,800 RMB, or €7,550.

There is of course a larger battery option, with 40.93 kWh, available for an MSRP of 76,800 RMB, or €9,860. Deals can bring this down to 69,800 RMB (€8,960). This has a CLTC rating of 401 km, which should translate to around 200 km at modest European highway/national route speeds in fair conditions.

The vehicle warranty on all variants is 3 years, 120,000 km, with 8 years on the battery.

Dongfeng Nammi 01

Dongfeng, the manufacturer of the Dacia Spring and the Nano Box twins, has just released a new model in the larger 4,000 mm class — the Nammi 01.

The Nammi 01 is another sub-compact crossover, with similar dimensions to the others we have detailed above (length 4,030 mm, height 1,570 mm). It has only been on the market for two months and is currently ramping past 1,000 units per month. It hasn’t yet made overseas sales.

The base variant has 31.45 kWh and 30 minute DC charging. CTLC rated range is 330 km, and the motor power is 70 kW. Pricing for this version is 74,800 RMB (€9,600). Deals can be had for 69,800 RMB (€8,960).

The Nammi 01’s interior has some interesting styling touches, especially given the price point:

There is a 42.3 kWh battery version also available which starts from an MSRP of 92,800 RMB (€11,900), although deals can be had for 88,800 RMB (€11,400). This one has a CLTC rating of 430 km, which should translate to at least 210 km real-world range at modest European highway speeds in decent conditions.

I don’t yet have vehicle warranty information, it is likely 3 years and 100,000 km, again with 8 years on the battery.

Since the Nammi 01 is the younger brother of the Dacia Spring, there’s every chance it could be badged under one of the brands of the Renault Group and be brought to the European market.

Wuling Bingo

Last but not least of the four models in this 4,000 mm segment is the big brother of the Wuling Mini, the Wuling Bingo, which launched in early 2023.

The Bingo is, unsurprisingly, of similar size to the others above (length 3,950 mm, height 1,580 mm), despite having a more cutesy front face that can give the impression of smallness:

The Bingo is already extremely popular in its home market, averaging almost 20,000 units per month. That’s 20x the volume of the Spring’s twin, the Dongfeng Nano Box!

The Bingo started shipping to Indonesia late last year, and likely will arrive elsewhere in SE Asia soon (some Wuling models already sell in Thailand, for example). There is no news yet about its spread further afield.

A mid-tier variant has a battery of 31.9 kWh and a DC charging time of 35 minutes. Its CLTC range rating is 333 km. This version has an MSRP of 73,800 RMB, or €9,470. Discount deals are around, for 65,800 RMB (€8,445).

There’s of course a bigger battery available with 37.9 kWh, with a CLTC rating of 410 km. This one’s MSRP is 88,800 RMB, (€11,395), with deals from 81,800 RMB, or €10,495.

All of these Wuling Bingo variants have motors with 50 kW and come with a vehicle warranty of 3 years or 100,000 km (and the usual 8 years on the battery).

Since the Wuling auto brand is co-owned by General Motors and SAIC (in their SGMW venture), there is a chance that a version of the Wuling Bingo might make it closer towards Europe at some point.

Loads More

Notice that all of the above 4 models have slightly bigger batteries than the Dacia–Dongfeng twins, but the Geometry E and the Neta Aya actually have MSRP prices below that of the 26.8 kWh Dongfeng Nano Box that is our benchmark! The prices of the newer Nammi 01 and Wuling Bingo are slightly higher, but still close and well within the ballpark for cross-shopping.

As should be clear by now, even more potential alternatives — which are almost as affordable — also exist. For example, the Bingo’s bigger (and less cutesy) brother, the “Bingo Plus,” is launching right now, with a length of 4,090 mm. It has a 37.9 kWh battery, “400km” CLTP option, with a likely deal pricing of not more than 89,800 RMB, or €11,500 MSRP.

There’s even a big brother to the Baojun Yep called — you guessed it — the Baojun Yep Plus at ~4,000 mm. This is expected to have a roughly 40 kWh battery and 400 km CLTC rating, and will have an MSPR of around 98,800 RMB, or €12,600. It looks quite stylish:

How Are These Low Prices Possible?

How are these low BEV prices achieved? Compared to what we become habituated to seeing in Europe, these seem to be magically low prices. But there’s no magic going on here, just the ongoing cost reductions of the key BEV technologies. These reductions have already been in progress for many years, are ongoing, and will continue into the future.

Recall that ICE powertrains are inherently complicated. This is unavoidable when trying to tame the high-pressure combustion explosions of volatile fuels for tens or hundreds of millions of cycles and clean them up to levels which reduce their toxicity and emissions. They have thousands of moving parts, many of which have to be assembled together in a way which endures cycles of very high temperatures and pressures over at least 100,000 kilometres (or more). All whilst warrantying the entire system.

BEV powertrains, on the other hand, have relatively few moving parts: the motor and the fixed reduction gear, plus a few cooling pumps, fans, and relay switches. The rest of the system has essentially no moving parts — mostly electrical circuits, transformers (and inverters), and software control. Temperature cycles are much milder than for ICE powertrains. There is no high-pressure block, nor great mechanical stress on components. BEVs powertrains are therefore much simpler to assemble to a level which provides reliability and warranty.

The only initially challenging aspect of cost for BEVs was the cost of batteries for a decent amount of energy storage, enough to make BEVs practical replacements for ICE cars. Even so, with increasing manufacturing scale, and efficiencies, and steadily improving energy density (per weight of constituent materials), the cost per unit energy of batteries has been reducing. The same cost reduction trend (price/performance ratio) is commonplace for technology products (think CPUs, solar panels, and more).

The longstanding guide-marker, since at least 2001 (see, e.g., Delucci & Lipman, 2001), has been that BEVs will “break through” to reach cost parity with equivalent ICE cars in most vehicle segments once battery costs (at the pack level) fall below $100 per kWh. We have discussed this $100 goalpost several times over the years as have analysts such as McKinsey & Company and BNEF, amongst many others.

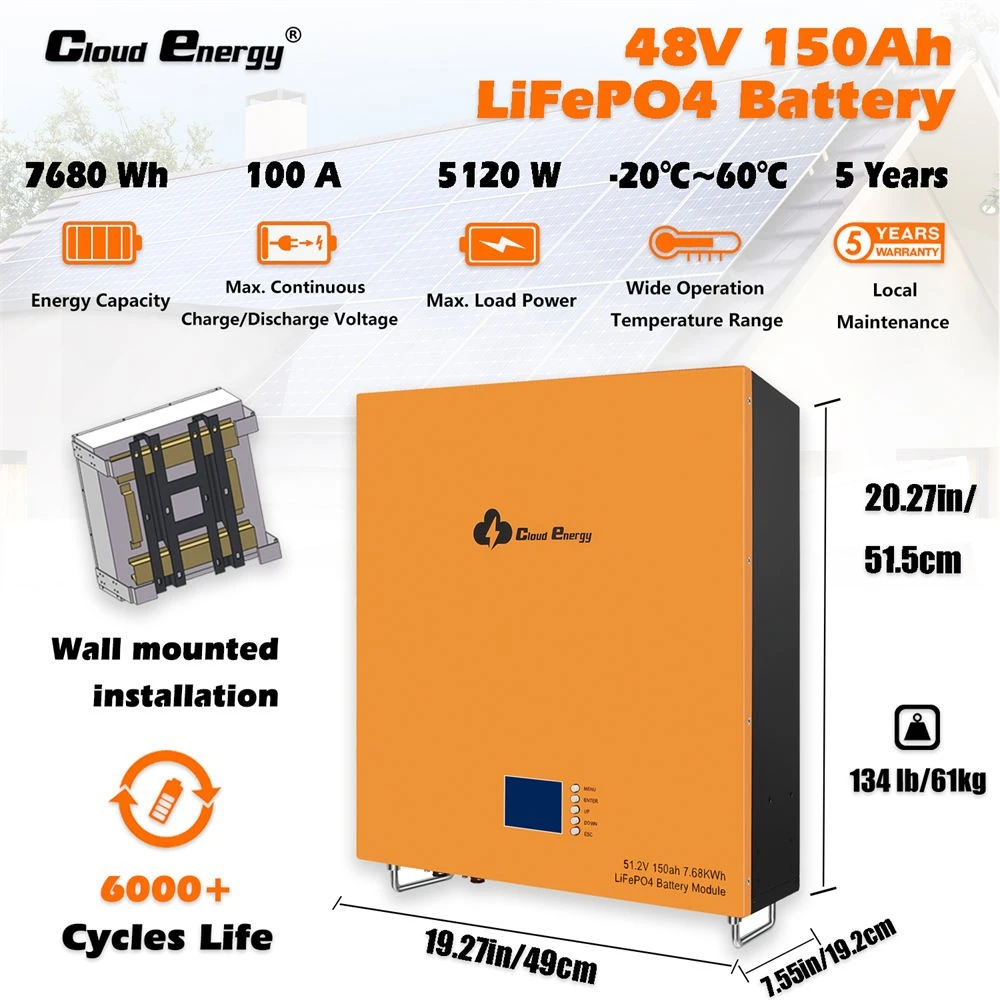

Most of the BEVs we have surveyed in this series use LFP cells. Lithium carbonate pricing temporarily spiked to 5× its long term norms between mid-2021 and Q3 2023, but has since returned to normal. In late January 2024, standard (VDA) format LFP cell prices fell to as low as 400 RMB (€52, $56) per kWh, which is around half of the price 12 months earlier, and prices are continuing on their long-term downward trend.

LFP cells are thermally stable and have very good cycle life. In modestly powered vehicles, the cells can get away with very simple cooling (active air cooling, or even passive cooling). This means that assembling cells into a pack adds at most 25% to the cost of the cells. With cells already passing below 400 RMB per kWh, this entails battery pack prices of 500 RMB (€65, or $70) per kWh, far below the $100 “breakthrough” level. The ~30 kWh LFP battery packs can therefore cost under €2,000.

While battery pack costs are the major component of BEV costs, the cost of other parts of the powertrain have improved greatly also. It’s now common for the electric motor, reduction-gear, and inverter to be packaged (and cooled) as a single unit, sometimes called a “3-in-1” electric drive unit, or “e-axle.” Some manufacturers go further, by adding the DC-DC converter, the onboard AC charger, and the power distribution unit to this integrated package (a “6-in-1” system). BYD’s latest designs also add in the BMS and the vehicle control unit (an “8-in-1” system). This integration further reduces the overall cost.

For the BEVs we have looked at (typically with modest peak power of 30 to 50 kW), the 3-in-1 drive system can cost well under €1000; in large volumes, perhaps under €750. So, combined, the cost of the battery pack and powertrain is under €3,000 in these BEVs and approaching €2,500. This is how they can be offered for sale at €8,000 to €9,000 and still be profitable.

Questions, Questions…

Note that the cells and drive units can be internationally traded at commodity pricing. So the question we should be asking is why aren’t there simple BEVs on sale in Europe at anywhere near these prices?

I intend to dig into this more in future parts of this series, but to start to answer it, we should remind ourselves of another question. Why did almost all of the international automakers, including the Europeans, turn their backs on the initial BEVs they started to demonstrate, lease, and sell — in small numbers — in the 1990s and drop most of their research into EVs? See the 2006 film Who Killed The Electric Car for some reflections.

We can also ask — why is there no real competition between European automakers to offer affordable cars (or any kind) any more, especially when simple economy cars under €10,000 were commonplace a few years ago? And how did European automakers make record profits in 2022?

Is the lack of affordable BEVs in Europe — by any legacy brands — just an accident? Has the attitude and internal culture of the legacy automakers really changed since the 1990s?

I’ve laid out some of the latest information here, and in the links, about the reality of BEV pricing trends outside of the European bubble. I’m sure that our readers have plenty of thoughts and more data to share about this. Please do share your insights and join in the discussion below — your input will inform the future articles in this series.